Fangs for Nothing: ‘Renfield’ Sinks Its Teeth into Cinematic Absurdity

Renfield, the latest cinematic monstrosity to emerge from the bowels of Hollywood, is a film that seems to have been concocted in the delirious throes of a fever dream — a fever dream that, I might add, would have been better left unremembered. Directed by Chris McKay, a man whose previous foray into the world of Lego Batman left me with a sense of existential dread, Renfield is a film that takes the hallowed vampire mythos and subjects it to a merciless vivisection, leaving us with a grotesque moviegoing experience that is as bewildering as it is banal.

The story is a macabre tale of the titular character, Renfield, a man caught in the thrall of his malevolent master, Count Dracula, a narcissistic dandy who revels in grandiloquence. Renfield is both endearing and pitiable, his loyalty to Dracula both his salvation and curse. The film’s narrative is a chaotic vivisection of the vampire mythos, a grotesque pastiche that leaves audiences reeling.

Theatrics & Eccentricities—A Study in Acting Extremes

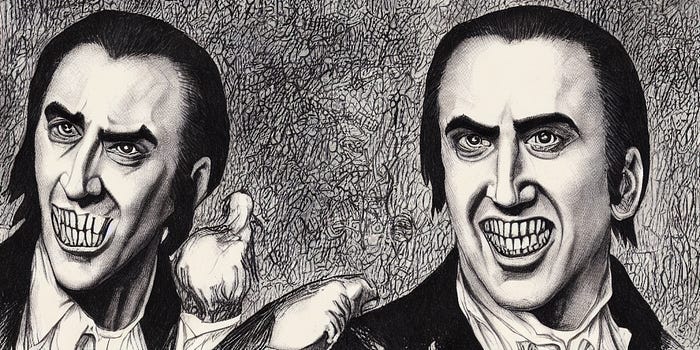

Nicolas Cage, that enigmatic and often inscrutable actor, takes on the mantle of Count Dracula with a flamboyance that borders on the absurd. Cage’s Dracula is a caricature of the macabre, a monster who revels in his own grandiloquence. His portrayal of the infamous count is a study in unbridled excess, a performance so ostentatious that it threatens to eclipse the very film itself. Cage chews the scenery with such ferocity that one fears for the structural integrity of the set. It is a performance that is at once mesmerizing and maddening, a spectacle that defies both reason and taste.

Nicholas Hoult, as the titular Renfield, provides a counterpoint to Cage’s theatrics, delivering a performance that is both endearing and pitiable. Hoult’s Renfield is a man caught in the thrall of his malevolent master, a man whose loyalty is cruelly paradoxical. And yet, despite Hoult’s commendable efforts, his portrayal of Renfield is ultimately overshadowed by the sheer bombast of Cage’s Dracula.

The supporting cast, a motley crew of misfits and ne’er-do-wells, is squandered with reckless abandon. Awkwafina, that erstwhile rapper-turned-actress, is given precious little to do, her talents wasted on a character as underdeveloped as she is unremarkable. Shoreh Aghdashloo, an actress of considerable gravitas, is similarly ill-served, her presence reduced to little more than a fleeting cameo. Ben Schwartz, as the bumbling crime lord Teddy Lobo, provides some much-needed comic relief, but even his efforts are undermined by the film’s tonal inconsistencies.

Sensory Overload—Chaos and Cacophony

The film’s setting, the storied city of New Orleans, is rendered with a lurid and lascivious eye — a city of sin and debauchery that serves as a fitting backdrop for the film’s orgiastic revelries. The cinematography, awash in a kaleidoscope of neon hues, is at once arresting and disorienting. The camera sweeps through the narrow streets of the French Quarter, capturing vibrant colors, pulsating lights, and the iconic wrought-iron balconies. A memorable scene unfolds during a Mardi Gras parade, where Nicolas Cage’s Dracula, adorned in a flamboyant costume, revels in the festivities. The camera captures the frenzied energy of the crowd, the flurry of beads, and the hypnotic rhythm of brass bands.

As the film delves into New Orleans’ dark underbelly, the cinematography takes on a sinister tone. Vibrant nightlife gives way to shadowy alleyways and dimly lit cemeteries, where the horror of the vampire mythos is unleashed. In a chilling sequence, Nicholas Hoult’s Renfield is lured into a dilapidated mansion, confronted by his vampiric master. Disorienting angles and eerie lighting heighten the foreboding. The mansion’s grand staircase and chandeliers cast an otherworldly glow, contrasting with decaying walls. As Renfield descends into madness, the cinematography mirrors his psychological descent with distorted reflections and fragmented close-ups. New Orleans transforms from a vibrant playground to a haunting labyrinth.

The film’s score, a cacophonous medley of discordant melodies composed by an avant-garde ensemble, only serves to heighten the sense of chaos and confusion that permeates the narrative. It is a soundtrack that, much like the film itself, is devoid of nuance and subtlety — a soundtrack that bludgeons the senses with its relentless cacophony. The score’s jarring transitions, atonal harmonies, and unsettling soundscapes create an atmosphere of unease, amplifying the film’s themes of madness and obsession. The music becomes an integral character, accentuating the film’s descent into the macabre and surreal.

A Frankenstein’s Monster of a Plot

The film’s narrative, if one can call it that, is a hodgepodge of disparate elements — a veritable Frankenstein’s monster of a plot that lurches and staggers its way to an ignominious conclusion. The screenplay, penned by Ryan Ridley, is riddled with scenes of gratuitous violence and gore, scenes that seem to exist solely for the purpose of titillating the basest instincts of the audience. It is a film that revels in its own depravity, a film that delights in its capacity to shock and appall.

And yet, for all its excesses, Renfield is a film that is curiously devoid of substance. It is a film that, in its quest for originality, loses sight of the very essence of storytelling. The characters are mere caricatures, the plot a thinly veiled excuse for a series of increasingly outlandish set pieces. It is a film that, in its pursuit of spectacle, forsakes the very elements that make cinema such a powerful and evocative medium.

Renfield is a testament to the decline of modern cinema, a film that epitomizes the vacuity and superficiality that have come to define the industry. It is a film that, despite its pretensions to grandeur, is ultimately little more than a hollow and soulless spectacle. It is a film that, for all its sound and fury, signifies nothing.

It’s a film that is both audacious and infuriating. It is a film that, in its quest for originality, stumbles headlong into the realm of the absurd. It is a film that, despite its moments of brilliance, fails to rise above the mediocrity that plagues the cinematic landscape. It is a film that, much like its titular character, is in desperate need of redemption — a redemption that, alas, seems forever beyond its grasp.

And yet, amidst the carnage and chaos, there are moments of genuine poignancy — moments that hint at the film that might have been. Hoult’s Renfield, for all his eccentricities, is a character of surprising depth and complexity — a character whose plight elicits both sympathy and revulsion. Cage’s Dracula, for all his histrionics, is a character of tragic grandeur — a character whose hubris is both his undoing and his salvation.

It is these moments, these fleeting glimpses of humanity, that ultimately redeem Renfield from the abyss of mediocrity. It is these moments that, in their quietude and restraint, serve as a stark counterpoint to the film’s frenetic excesses. It is these moments that, in their unassuming simplicity, remind us of the transformative power of cinema — a power that, even in the darkest of times, has the capacity to illuminate and inspire.

A Cinematic Chimera

In the final reckoning, Renfield is a film that defies easy categorization — a film that, for all its flaws, remains a singular and idiosyncratic work of art. It is a film that, in its audacity and ambition, challenges the conventions of the genre — a film that, in its unapologetic embrace of the absurd, transcends the limitations of its medium.

As I pondered the film’s myriad contradictions, I was struck by a sense of profound ambivalence — an ambivalence that, in its complexity and nuance, is emblematic of the film itself. For Renfield is a film that, like the enigmatic figure of Dracula himself, exists in a liminal space between light and darkness, between the sublime and the ridiculous, between art and artifice.

It revels in its own contradictions, a film that delights in its capacity to confound and provoke. It is a film that, in its gleeful subversion of genre conventions, exposes the inherent absurdity of the vampire mythos — an absurdity that is at once comic and tragic, grotesque and sublime.

But in its unrelenting quest for novelty, it eschews the trappings of traditional narrative structure — a film that, in its anarchic disregard for coherence and continuity, embraces the chaotic and the irrational. It is a film that, in its exuberant celebration of the carnivalesque, revels in the grotesque and the macabre — a film that, in its gleeful mockery of the sacred and the profane, exposes the folly of our most cherished beliefs and convictions.

It is a film that, in its audacious fusion of horror and comedy, blurs the boundaries between the real and the fantastical, between the mundane and the miraculous. It is a film that, in its playful exploration of the liminal spaces between life and death, between sanity and madness, between reason and unreason, challenges our most fundamental assumptions about the nature of reality and the limits of human experience.

In its exuberant celebration of the carnivalesque, it revels in the grotesque and the macabre — a film that, in its gleeful mockery of the sacred and the profane, exposes the folly of our most cherished beliefs and convictions.

And yet, for all its iconoclastic bravado, Renfield is a film that is ultimately undone by its own excesses — a film that, in its relentless pursuit of shock and spectacle, loses sight of the very qualities that make cinema such a potent and evocative medium. It is a film that, in its unbridled embrace of the absurd, forsakes the subtlety and nuance that are the hallmarks of true artistry — a film that, in its cavalier disregard for the conventions of storytelling, squanders the opportunity to explore the rich and complex tapestry of the human condition.

Ultimately, Renfield is a film that, like its titular protagonist, is both a victim and a perpetrator of its own excesses — a film that, like the tragic figure of Dracula himself, is both a product and a reflection of the cultural zeitgeist from which it emerged. It is a film that, for all its flamboyant theatrics and overwrought histrionics, remains a curiously hollow and insubstantial spectacle — a film that, for all its sound and fury, signifies little more than the vacuity and superficiality of the age in which we live.

The Paradoxical Charm of ‘Renfield’

And yet, despite its many shortcomings, Renfield remains a film that is not without its charms — a film that, for all its flaws, possesses a certain irreverent and anarchic spirit that is both refreshing and invigorating. It is a film that, in its unapologetic embrace of the absurd, serves as a potent and timely reminder of the transformative power of art — a power that, even in the face of adversity and despair, has the capacity to challenge, to provoke, and to inspire.

In this regard, Renfield is a film that, like the enigmatic figure of Dracula himself, remains an enduring and indelible presence in the cultural imagination — a presence that, like the immortal count himself, continues to haunt and to fascinate, to seduce and to beguile. And for that, at least, it is a film that deserves our grudging admiration and, perhaps, even our reluctant applause.

For Renfield is, in many ways, a cinematic chimera — a creature of disparate and incongruous parts, a creature that defies easy classification and resists facile interpretation. It is a film that, in its restless and relentless quest for novelty, challenges the boundaries of genre and subverts the conventions of narrative. It is a film that, in its audacious and unorthodox approach to storytelling, invites us to question our most deeply held assumptions about the nature of art and the function of cinema.

And yet, for all its iconoclastic posturing and avant-garde pretensions, Renfield is a film that is ultimately constrained by its own limitations — a film that, in its dogged pursuit of the new and the novel, is unable to transcend the very tropes and clichés that it seeks to subvert. It is a film that, in its fervent desire to shock and to provoke, often succumbs to the very excesses and indulgences that it purports to critique.

But perhaps this, too, is part of the film’s peculiar and paradoxical charm. For Renfield is a film that revels in its own contradictions and delights in its own ambiguities — a film that, in its playful and irreverent exploration of the vampire mythos, invites us to reconsider our own relationship to the fantastical and the macabre. It is a film that, in its gleeful and exuberant celebration of the carnivalesque, reminds us of the transformative and redemptive power of art — a power that, even in the darkest and most despairing of times, has the capacity to illuminate and to inspire.

The Decline of Western Civilization: The ‘Renfield’ Years

And so, as I reflect on the curious and confounding spectacle that is Renfield, I am reminded of the words of the great poet John Keats, who once wrote that “a thing of beauty is a joy forever.” And while Renfield may not be a thing of beauty in the conventional sense, it is, in its own peculiar and idiosyncratic way, a thing of joy — a joy that, like the immortal count himself, endures and persists, defying the ravages of time and the vicissitudes of fate.

In this regard, Renfield is a film that, for all its flaws and foibles, remains a testament to the indomitable and irrepressible spirit of the human imagination — a spirit that, like the enigmatic figure of Dracula himself, continues to haunt and to enchant, to captivate and to compel. And for that, at least, Renfield is a film that deserves to be celebrated and cherished — a film that, like the immortal count himself, will no doubt continue to cast its long and lingering shadow over the cinematic landscape for many years to come.

Still, as I left the theater, I was struck by a profound sense of melancholy — a melancholy born of the realization that Renfield ultimately represents the nadir of a once-noble art form. It is a film that, in its garish excesses and wanton disregard for narrative coherence, embodies the very antithesis of cinematic artistry. It is a film that, in its unrelenting pursuit of the lowest common denominator, betrays a fundamental contempt for its audience — a contempt that is as palpable as it is disheartening.